Not long ago, I spent several pleasurable days wandering the clean, well-ordered streets of Singapore. Aside from being a fantasyland for lovers of street food (the reason for my visit), the little city-state on the tip of the Malaysian Peninsula is known as the world capital of crackpot, Bloombergian-style nanny-state initiatives. It is illegal to not flush a public toilet in Singapore (the punishment is a steep fine), or to wander naked in your apartment without the shades drawn. But like lots of New Yorkers who are conditioned, when they travel, to desperately scatter the extra change in their pockets to an array of puzzled doormen, cabbies, waiters, and touts, what I noticed most about Singapore was the strange, blissful absence of tips.

Tipping is not illegal in Singapore, but, like almost everywhere else in the world except the U.S., it’s not actively encouraged either. The bellhop at my hotel did not loiter expectantly, waiting for his extra $5. There were no tip jars cluttering the counters of the noodle stands I visited, and instead of tips, sit-down restaurants generally added a 10 percent service charge to my bill. When I timidly offered an extra couple of bucks (the equivalent of roughly 50 cents in U.S. currency) to the cabbie who drove me in from the airport, he practically shook my hand with gratitude. “Thank you, sir,” he cried, “but remember, here in Singapore, tipping is not required!”

Emboldened by this curiously bracing experience, I decided to conduct a rash experiment when I returned home to the tipping capital of the USA, and therefore arguably of the entire universe, New York City—which also happens to be in the midst of a genuine tipping mania. I would try to dispense cash based on merit rather than out of obligation, or macho self-satisfaction, or that hovering, vaguely conflicted sense of guilt that many of us neurotic New Yorkers feel when it comes to reaching into our pockets for an extra buck or two. I would not tip taxi drivers unless they were efficient and courteous. I would not leave errant change in the tip bucket of my local barista (or flower stand, or taco shop) just because the tip bucket was there. Most scandalous of all, I would not automatically leave the ritual 20 percent gratuity in restaurants, even though I’m usually on an expense account and often leave more than that.

On the first morning after my new resolution, I avoided the garage guy and the barber, and managed to stifle the reflexive urge to scatter coins in the buckets at my local coffee shop. My first taxi of the day was driven by a grim-faced gentleman named Mr. Arip. The air conditioner in Mr. Arip’s cab was broken, and unlike the loquacious cabbies of Singapore, he drove along the rutted avenues in stony silence. When I declined to tip him on a fare of $10, he glared at me so furiously that I looked down at my shoes and exited the cab while pretending to natter on my cell phone.

At the restaurant that evening, my companions and I were seated at a cramped little table next to the clamorous bar. As our meal progressed, the noise level rose, time dragged between courses, and one dish we ordered never arrived. But when I wondered out loud whether these challenging conditions were grounds for less of a tip, or even no tip at all, my fellow diners looked at me with quiet horror. “I think our waiter is very nice. I think you should leave her a big tip,” one of them said in the tone my mother used to use, long ago, when she wanted me to finish my peas. So when the bill arrived, I did what New Yorkers are conditioned to do in this increasingly anxious, tip-saturated age. I took out my pen, calculated the usual 20 percent, and meekly signed the check.

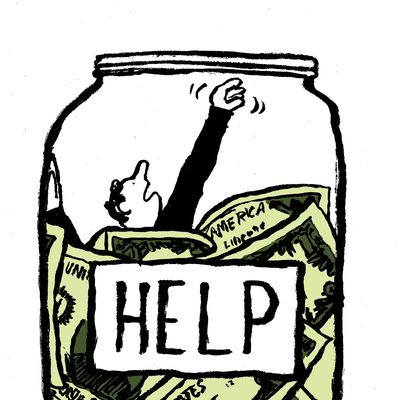

A friend of mine, whose views on America’s current tipping epidemic have been shaped by long hours spent slaving for an hourly wage in professional kitchens around town while the glib, glad-handing servers in the front of the house pocket the lucrative tips, has a phrase for this kind of sheepish, counterintuitive behavior. “You’re a tip zombie,” he says. “It’s like a disease. We can’t help ourselves.” Never mind that studies have shown that tipping rarely results in better service (if you want the royal treatment, tip very, very well before dinner or while checking into your hotel) or that it’s arguably racist (studies have also shown that nonwhites make less in tips) and sexist (women make better tips than men, but, according to a report by the Restaurant Opportunities Center United, 90 percent of them are harassed for their trouble). Never mind that many economists regard tipping as inefficient (according to another report, by the Community Service Society, New York State employees in tipping professions are much more likely to live below the poverty line than those who aren’t). Americans are powerless when it comes to the ancient, seductive, institutionalized myth of the 20 percent tip.

Not so very long ago, 10 percent was the ritual amount New Yorkers left on top of their restaurant bills, but many big-city high rollers now consider 20 percent to be a little cheap. At my favorite neighborhood coffee shop, Joe’s, there used to be one tip jar brimming with dollar bills, but now there are two, one where you order and pay, and one where you pick up your $4 iced latte. “I don’t remember seeing tip jars at a hot-dog stand when I was a kid growing up in New York, but now they’re everywhere,” says Steve Dublanica, who worked for years as a waiter and runs the popular industry website Waiter Rant. Dublanica has also spied tip jars in casinos and even in the men’s-restroom trailers at county fairs. “Tip creep” is his name for this phenomenon, which he says tends to happen, historically, when times are tough. As corporations scrounge for profits and the explosion in low-paying service jobs spreads through the post-crash economy (low-paying service positions accounted for 44 percent of recovery job growth), it’s creeping across the country, too. The Marriott hotel chain recently joined an education campaign (fronted by Maria Shriver) to teach guests appropriate tipping practices for their legions of housekeepers, presumably in lieu of a wage hike. Envelopes are Marriott’s preferred method for extracting gratuities, but every few weeks there seems to be another salvo of easy-swipe technology that makes it simpler than ever to part, semi-voluntarily, with a few extra bucks. According to data collected by the city’s Taxi and Limousine Commission, after credit-card machines were installed, the new technology resulted in riders’ paying a 22 percent credit-card tip, on average, compared with 10 percent when cabs were cash only. If you ride with Uber, you’ll find a service fee already baked in. A start-up called DipJar, now in use around town, lets you swipe your credit card in lieu of dropping some change into an actual tip bucket. Starbucks now has an iPhone app that has its own “digital tip function,” which will remind customers after each purchase to “share your appreciation for your favorite baristas.”

Nowhere, however, is this endlessly mutating ecosystem of gratuities and handouts more conspicuous or controversial than in the Byzantine world of full-service restaurants, which in recent years has become a battleground in America’s great tip debate. Or so it occurred to me when I spent the evening, not long ago, hanging around the dining room of a popular Manhattan establishment that—thanks to the complex legal ramifications that surround tipping in New York—we’ll call Buzbie’s.

In exchange for giving the wait staff access to the evening’s lucrative tip-pool bounty (which tonight will total $2,467 on sales of $12,830, plus a possibly undisclosed amount of cash), the owners of Buzbie’s are allowed to pay their front-of-the-house employees—like the bartender, whom we’ll call Keith, and the gregarious part-time actress, whom we’ll call Sophie—$5 an hour for their first 40 hours of work per week, or $3 below minimum wage. (Tip pools tend to pop up at higher-end restaurants; elsewhere, servers simply pocket what they bring in.) This so-called tip-credit law, which was passed during the ’60s in a halfhearted attempt to extend the minimum wage to the hazy, underground, billion-dollar world of the tipped professions, is fraught with all sorts of legal, moral, and political complexities. This hourly wage varies from one tipping profession to the next, and some states allow it while others, like California, don’t. The tip pool can be divided up only by employees who deal directly with tipping customers, which opens up restaurant owners to class-action lawsuits if the tips aren’t handled properly and leaves the increasingly prominent and restive kitchen-slave community out in the cold.

With the rise of the tattooed TV chef over the past decade, however, a backlash has been brewing. Several high-profile restaurants, like Thomas Keller’s Per Se, have gone to a European-style service-charge model. Sushi Yasuda in midtown has done away with tipping altogether. In an impassioned anti-tipping screed in the Times last year, restaurant critic Pete Wells called the standard tipping practices at most restaurants “irrational, outdated, ineffective, confusing, prone to abuse and sometimes discriminatory.” Non-tip-pool restaurants have begun popping up around the country, not just in tony places like Berkeley (Chez Panisse) and Lincoln Park (Grant Achatz’s Alinea), but in such towns as Newport, Kentucky, where Bob Conway, who owns dozens of T.G.I. Fridays, has taken the radical step, at his new non-tip, beefcentric establishment called Packhouse Meats, of paying his servers $10 an hour, or 20 percent of their food sales per shift.

The owner of Buzbie’s says he’s aware of the grumblings emanating from the kitchen (his chef is a co-owner), but he compares putting together a talented wait staff to casting a movie, and he’s wary of disrupting that alchemy. But even if he wanted to, it’s not technically legal in New York to charge a blanket service rate for fewer than eight people, and such a change would bring a much higher federal tax bill. He agrees with another prominent restaurateur I talked to, who said that “while the system is imperfect, it’s not imperfect enough to change.”

This is fine with Keith the bartender, who’s well aware that the bar is one of the main tip engines of any restaurant, because it’s generally populated by men, who tend to be better tippers than women (they run up larger tabs, just like in the dining room) and a good portion of the tips are in cash, which, as every restaurant veteran knows, rarely gets reported to the taxman. Many of the big tippers are gentlemen who wear suits and favor simpler drinks over newfangled mixologist creations, but the biggest tippers of all are the regulars. On the flip side of this, Michael Lynn of the Cornell School of Hotel Administration, who has been pondering the subject of tipping for more than three decades, says that alcohol consumption tends to increase tips. (Servers say there is a point of diminishing returns: Soused customers often have trouble calculating their bills.) Men tend to tip women servers better; women, in turn, lavish similar largesse on waiters as opposed to waitresses.

Sophie, who was one of Buzbie’s most efficient and popular servers (but has since left for another busy, prosperous restaurant in the neighborhood), takes home roughly twice as much as the salaried manager. At Buzbie’s, tips are divided according to your position on the floor (the people with the greatest proximity to customers get the highest percentage of the tips). Over time the less efficient tip-getters tend to be weeded out. Like anyone who flourishes in this Darwinian system, Sophie is adept at reading her customers for psychological cues. She watches the way people sit down to dinner. (“If it takes them a little while, they’ll need some extra coddling.”) If they’re talking animatedly, she’ll take some time before bringing the menus. (“The second you rush a table, it stops being about them.”) Men love to be made fun of, but only when they’re out with other men, and if it’s a couple, it’s the woman you have to flirt with, not the guy. (“Girls will change tips.”)

According to Tipping: An American Social History of Gratuities, by Kerry Segrave, the habit of leaving gratuities for servants became popular in the West in the grand houses of England during Tudor times. Tipping didn’t become popular in this country until the mid-1800s, when traveling grandees brought the custom back from Europe. There was plenty of opposition to the practice in the early going. Customers in hotels, restaurants, and on the nation’s trains (the Pullman company was notorious for recruiting ex-slaves to angle for tips) quickly grew tired of being pestered for extra cash. Labor leaders like Samuel Gompers complained, as anti-tipping advocates do today, that the practice was a convenient excuse for owners not to pay their workers a proper wage. By the 1940s, in Continental Europe, a full-blown anti-tipping movement was under way, although in this country the trend moved stubbornly in the opposite direction.

Hardheaded number crunchers like John D. Rockefeller Jr. (like lots of self-made billionaires, a reluctant tipper) have always thought tipping a dubious, inefficient practice. “But for a psychologist, it’s a little bit easier to understand,” Lynn says. Tipping tends to happen in what he calls “highly personalized” professions—we tip waiters and hairdressers but not doctors, lawyers, or flight attendants—and for several basic reasons. “People tip because they want to help servers, or cabbies, or delivery guys make what they think is a decent wage,” he says. “They tip to gain some kind of preferential service going forward at their barber, or favorite restaurant or bar, although studies show that doesn’t always happen, and they tip to gain or keep some idea of social esteem.”

This last point, according to Lynn, is the biggest reason Americans tip: Everyone else is doing it, and they’re afraid, like I was, as my pen quivered uncertainly over the check during my failed anti-tipping experiment, of looking like a fool. “At some point, tipping becomes the descriptive norm, and not just servers but consumers start to look down on non-tippers,” he says. This tends to result in hefty doses of guilt and high anxiety. “I tip 10 to 15 percent in a cab, but I feel guilty and always wear a seat belt,” said one high-powered Manhattan lawyer as she ticked off her impressively neurotic tip-zombie routine. “I tip 20 to 25 percent in restaurants, because lots of times they know me. I tip 20 percent for nails and hair because these people can affect your health if they don’t like you and because New Yorkers have to look good. I tip $1,000 to the 30 people in my building every Christmas. I tip the garage guys at Christmas, too, and give them a dollar when they get my car. Is that enough? Am I being cheap?”

The tipping world is full of stories of retribution for non-tippers and cheapskates, and many of the most hair-raising tales come from the hotel industry, which is a veritable ecosystem of tipping psychosis. In his book Heads in Beds, Jacob Tomsky relates what he swears is the true story of an irate New York bellman, who, after lugging bag after bag to an unnamed celebrity’s room without getting a tip in return, snuck back later that evening to urinate in the celebrity’s yellow bottle of cologne.

When Tomsky worked the front desk at a midtown hotel, he would put bad tippers, and otherwise unpleasant individuals, in room 1212, where the phone tended to ring off the hook when other hotel guests forgot to dial 9 for an outside line. To prevent the bellmen from pissing in your cologne, he suggests never tipping less than the price of a beer. He recommends tipping hotel car valets handsomely, because he’s worked as one, and has seen them purposely over-rev engines, and stick wads of gum under the car seats of under-tipping guests. But the best way to improve your stay at any hotel, Tomsky says, is to slip the desk agent a few dollars as you check in. “I’ve upgraded guests for three nights after a friendly smile and an extra $20. That’s almost $300 on a $20 investment, which is a pretty good deal.”

As the level of tipping anxiety has reached a mania over the years, canny proprietors have found all sorts of subtle ways to enhance their take. If a server wants a larger gratuity than usual, Lynn says, it helps to squat tableside and to establish eye contact with customers. The most deadly “tip magnets,” Lynn’s research not surprisingly shows, are slender, blonde, attractive large-breasted women in their 30s, who—so he speculates—are more appealing to their customers than women who are older and less threatening than bombshells in their 20s.

This isn’t news to Sophie, who is slender and blonde and happened to turn 32 recently. When she’s not waiting tables, she’s an accomplished actress, with credits at theaters around the country and on Broadway. The biggest tip she ever saw was from Matt Damon, who left $500 on top of a $600 meal. But those big payoffs are like strikes of lightning. To make an average of 22 percent in tips night after night, as Sophie does, requires endless reservoirs of positive energy and a cagey psychological awareness. “We actors don’t wait tables because we’re dumb-dumbs or because we’re unemployable,” she says. “We’re good at divining what people want and giving it back to them.”

The tables at Buzbie’s are full now, and Sophie has her eye on two dignified, potentially problematic women of a certain age who are just sitting down. Already they’ve complained about the location of their table (by the bar) and the noise. They’ve asked if they could share food, which is not an ideal cue where tips are concerned, and whether it would be possible to order off the menu (it isn’t). To “turn them,” as she delicately puts it, Sophie plans to shower the women with little kindnesses. “Younger girls want you to be their BFF, but ladies just want to be treated like ladies,” she explains. Sophie will not try to oversell certain dishes. (“You milk people on the expensive crap and they won’t come back.”) She will speak to them as equals (“You have to make clear you’re not some dumb waitron”), and she may even resort to an extra splash of wine.

Like most servers who’ve come to rely on tips for their livelihood, Sophie’s not a fan of the European service-charge model at some of the hoity establishments around town. She’d make less money. It turns out that most Americans agree with her, but for a different reason. “People consider the service charge to be an involuntary tip,” Lynn says. Still, chefs at those fancy service-charge places report that their customers routinely leave extra cash on top of the mandated percentage. Tipping may be more or less automatic, but the most seductive, potentially addictive tip-zombie quality of all just might be the illusion of control.

Even the most vociferous anti-tip-pool advocates admit that the great kitchen-slave tipping revolution still has a long way to go. After a story in Slate last summer compared tipping to outright bribery, among other unsavory things, high-profile chef-restaurateurs like Danny Meyer, Tom Colicchio, and David Chang announced on Twitter that they were exploring ways of, as Chang delicately put it, “removing tips w/o revolt.” But a year later, the old tip-pooling system is still in place at all of their restaurants, and the service-charge model is generally restricted to smaller, more effete establishments populated by international gastronauts who are less sensitive to high price points than to the fickle winds of culinary fashion. At Packhouse Meats down in Kentucky, Bob Conway recently told a reporter from the Louisville Courier-Journal that he and his non-tipping restaurant were getting pummeled by agitated Yelpers who accused him of taking advantage of his employees by not letting them supplement their incomes the old-fashioned way, through the skewed bounty of tips.

Meanwhile, back at Buzbie’s, a new crowd of customers is settling in. Sophie is moving around the room in a practiced, efficient way, showering her customers with positive, tip-generating karma. The two potentially problematic women at table nine are chatting happily now, and to encourage their happiness she’s given one of them an extra splash of white wine. When they finish their meal (soft-shell crabs, a burger, a shared salad), they split the check with two corporate cards and stop for a short exit interview. Their names are Eileen and Paula, and they enjoyed their dinner, even though the room was a little noisy. Paula left a tip totaling exactly 20 percent of her bill, because that’s what she always does, and Eileen left 2 percent more. Eileen says she liked the waitress, who was “lovely and professional” and knew to give her an extra swig of wine just when she needed it. She wanted me to know that, unlike a lot of people, she was a discerning, circumspect tipper. “I’m a New Yorker,” Eileen says as she walks out the door. “I’ve never left 10 percent, but I’ll leave under 20 percent if somebody’s an asshole.”

After Eileen leaves, I sit at the bar for a time, sipping a beer, watching the characters in this timeless little drama come and go. The owner drifts by, a smiling, beneficent presence in his brightly patterned shirt. Keith the bartender has disappeared back to another restaurant in the building and is pouring $14 cocktails behind a crowd of revelers. Out on the floor, Sophie greets the new customers coming in and hops from table to table, laughing at jokes with her new friends, suggesting menu items, doling out lethal splashes of wine. The restaurant’s manager comes by to say hello, and when the subject of tips comes up, he shakes his head and laments the profusion of tip buckets at, among other places, his local dog salon. He grew up in a non-tipping culture, and as we survey the dining room, filled with tip zombies dutifully calculating their 20 percent, he observes that the practice seems to be on the rise even in his formerly tip-free homeland. “I think it’s because we have a lot of Americans on vacation there now,” he says with a sigh. “Personally, I think it’s all gotten a little out of hand.”

Related:

What Tips Mean to Servers, Bartenders, Doormen, and Baristas

Adam Platt Talks Tipping on CBS This Morning

The Art of the Money-Flirt

11 Restaurants Where Tipping Isn’t Customary

*This article appears in the November 3, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.